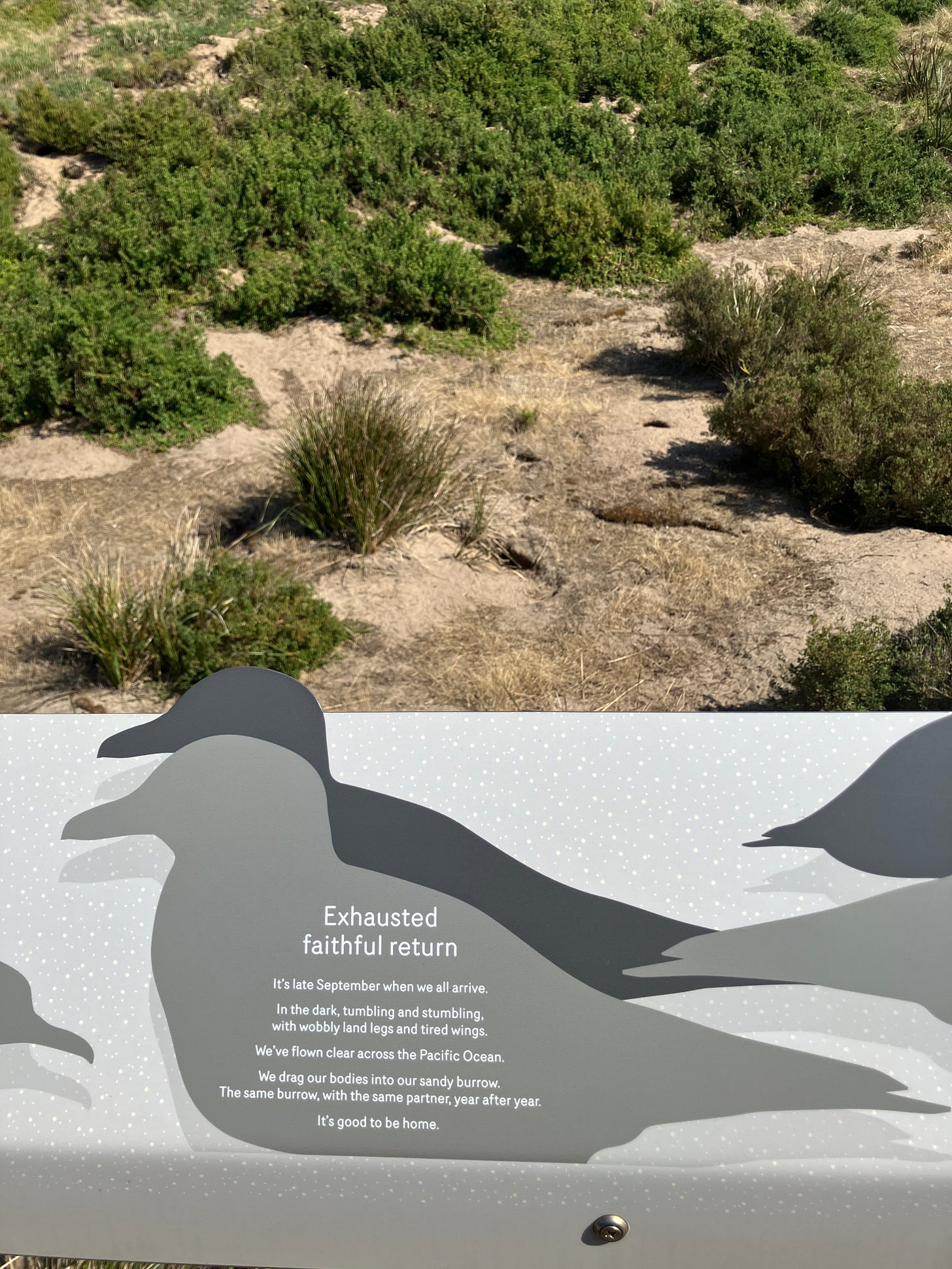

'Exhausted faithful return'

After an interpretive sign at lunawanna-alonnah / Bruny Island, lutruwita / Tasmania.

Sicklebodied birds course offshore in their streams. The Short-tailed Shearwaters glow lambent in the austral sunset as they skim across the horizon at the limits of sight. The arcing seabirds draw invisible threads over the ocean’s vast loom, weaving weft across the warp of the heaving sea.

Strong, terse wingbeats propel their maneuvering just above the waves. Turning side to side, they glide so low that, true to their name, the feathers on the ends of their wings slice the surface. Like a leisurely hand draped over a gunwale, fingertips dipping into the current.

After days at sea gathering food, these shearwaters are nearing shore in preparation to returning to their nest burrows. They have chicks to feed, but it’s not safe for a seabird to attempt a landing in the daylight hours—predators will be watching. The sun sinks toward the waves, hastening the hour of the twilight ritual that restages an annual return.

It’s late September when we all arrive.

They flew here from distant northern waters. From the far side of the Pacific—from Kamchatka, from Alaska; from Arctic seas—the Bering, the Chukchi, the Beaufort—every year the Short-tailed Shearwaters cast over and back across the tilt of the earth.

When the nesting time comes they return to these shores—the only land they have ever known—in testimony to navigation beyond human reckoning.

By moving between hemispheres, these transequatorial migrants live in a world without winter. When the boreal autumn comes to Alaska, the world population of Short-tailed Shearwaters turns south, traversing the perpetual summer of the equatorial Pacific to arrive at the austral spring.

To certain bluffs along the shores of southeastern Australia congregations of shearwaters return year after year. Off the southeast coast of Tasmania, which is an island off the southeast coast of mainland Australia, which is itself an island off the southeast coast of the world, lies the 140-square-mile Bruny Island: two landmasses of sclerophyll forest, dry pasture, and hilly jungle joined by a long, narrow isthmus called the Neck. At the narrowest point on the miles-long Neck, where the island’s spine tapers to some five hundred feet across, Bruny Island’s central ridge slopes down toward the sands.

Burrow holes dot the earth above the dunes. Dark, dusty little caverns worm into the slope between salt-hardy shrubs anchoring bare dirt. Sparse grasses trembled in the midsummer breeze. To the west, the mountains of Tasmania rose across a placid strait; to the east, the long rollers of the Tasman Sea, where the Pacific Ocean meets the Southern Ocean, crashed onto a broad crescent of a beach.

I craned my neck to try to peer deeper inside the nests. I knew that shearwater chicks must huddle somewhere within, but all I could see was shadow. Instead I read an interpretive sign affixed to the boardwalk by the state parks authority.

In the dark, tumbling and stumbling, with wobbly land legs and tired wings.

The seabirds of the order Procellariiformes—from the Latin for a storm, a tempest—diverged from their closest relatives, the penguins, sixty million years ago. These tubenoses, so nicknamed for a nasal gland on the bill that excretes the ocean’s salts, live their lives roaming the seas: They take their rest on the water, forage by diving for squid or plucking surface fish, and glide across great distances in long stretches of effortless flight.

A superficial resemblance to the familiar seagull—mere evolutionary coincidence—is shattered at the sight of a shearwater in motion. Their elegance is extraordinary, their speed dazzling. An individual in the swarm slips the grasp of the eye in a second.

Though agile in the air and adept in the water, shearwaters are utterly unequipped for land. But it is the only place where new shearwaters can be made. They must come ashore to breed, and it is the only time they do. They must return to the closest thing an ocean-spanning bird has to a home.

From ancient sites on the southern coasts the young are hatched and reared. They pierce their way out of the egg as lumpy gray fluff, and reared on the regurgitated sealife their parents bring, they emerge from the burrow to spread wings that will carry them to join the flock at sea.

We’ve flown clear across the Pacific Ocean.

In their multitudes—thirty million individuals returning to hundreds of colonies, many of which host millions of burrows—the Short-tailed Shearwaters spend their lives astride the currents that cross the ocean’s great spaces. In an environment where sight and hearing are no use in orientation, they follow ephemeral gradients of scent to food: Trace molecules of chemicals emitted by their prey guide shearwaters at sea across invisible gradients.

Outside the breeding season, many other seabirds—the albatrosses, for example—are solitary wanderers. But the Short-tailed Shearwater is as gregarious asea as it is ashore, congregating in flocks as great as twenty thousand. When foraging they sometimes mass many thousands strong with gulls, cormorants, terns, even humpback whales. In pursuit of prey they plunge into the water, diving as deep as two hundred feet where the light dims.

Over the course of the twentieth century, shearwaters were killed by the tens of millions as bycatch from industrial fishing—hooked on long lines, snared in nets. In the twenty-first, marine heat waves of uncommon frequency and intensity deplete food sources on their northern foraging grounds. Plastics fill their stomachs. Feral cats snatch their young. Short-tailed Shearwaters still die by the many thousands each year.

Thousands of them washed ashore in Alaska in the summer of 2019 following several years of die-offs. Hundreds of thousands were thought to have died that season. Necropsies indicated that they had starved. That September, the mass return of the Short-taileds to southeastern Australia failed to materialize.

On the side of the road to the beach lie the dead birds with small dark bodies and dreadful long wings. I cannot see what they are and do not want to. I tell myself they could be magpies; they could be lapwings; they could be any bird other than—more dispensable than, somehow—a shearwater. I watch a pair of ravens perform their ministrations over an indistinct corpse.

We drag our bodies into our sandy burrow. The same burrow, with the same partner, year after year.

Short-tailed Shearwaters were and are known to Aboriginal Tasmanians as yolla. Parent shearwaters bring the nutrients of the sea ashore, and the chicks concentrate them in the valuable animal protein of their bodies. Aboriginal Tasmanians traditionally harvested them—reach into a burrow, pull out a yolla chick, snap its neck with a shake of the arm—and white settlers followed. Their distinctive oily flavor earned them the English nickname of “muttonbird.” Muttonbirding continues today, mostly in small government-licensed, Aboriginal-run commercial operations. With largest colonies hosting millions of pairs, the take of even thousands of young does not have a significant impact on the population.

During the migration back to these breeding islands, the shearwaters stream in from the sea to gradually repopulate the colonies’ burrows. But before the nesting period begins in earnest, the females venture back out to feed at sea before settling in to lay eggs. Their mates join the pre-laying exodus, and the colony is vacated entirely for weeks.

They return all at once and all on time. Overwhelming unison and astonishing consistency, a long-renowned ornithological curiosity. In modern quantitative terms, the timing exhibits “little variation between colonies or years,” with “85% of eggs laid within three days” of a mean falling between November 25 and 26, Carboneras et al. write for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

The full scale of the sight, though, is said to defy description: “It is not in my power to describe the scene that presents itself on the night of the 24th of November,” the nineteenth-century Tasmanian newspaperman John George Davies once wrote. “A few minutes before sunset, flocks are seen making for the island from every quarter, and with a rapidity hardly conceivable; when they congregate together, so dense is the cloud, that night is ushered in ten full minutes before the usual time.”

The spectacle has diminished since then, even within living memory. Douglas Mansell retired in 2015 after fifty years of muttonbirding with his extended family. “There used to be a million come in here, and you couldn't see the sky,” Mansell told the national broadcaster then. “Now they come and they certainly blacken the sky, but nowhere in the numbers that they used to.”

Any one shearwater, in its lifespan of a couple decades, would not see the changes in a colony thousands of years old. Yet these birds know the breadth of the Pacific at the same time that they know a particular burrow in the ground.

A shearwater knows a place that is for returning to. It knows its mate. It is faithful to another of its kind, and the pair know exactly where and when to find each other. Every year, the time comes, and they come to the place.

It’s good to be home.

These angels of the outer seas—their slender forms slice the horizon, shear the waters, out there at the limits of shorebound senses. Coursing along, cavorting in mirage, shimmering their way in from the sea.

Their exhausted faithful return spans an ocean, spans a hundred thousand lifetimes. Peregrine lives swarming in common impulse. Joy and duty alive between wingtips.

Beautiful <3