Seven sketches from iNaturalist

Online images of birds in places.

I’ve spent a decent amount of time identifying user-uploaded photos of North American birds on the community science website iNaturalist. Sometimes I come across observations that I save to my favorites because they show an interesting individual, behavior, or habitat. Here’s a selection of images that evoke a sense of a place in which I wish I could be, and some words about what they make me think about.

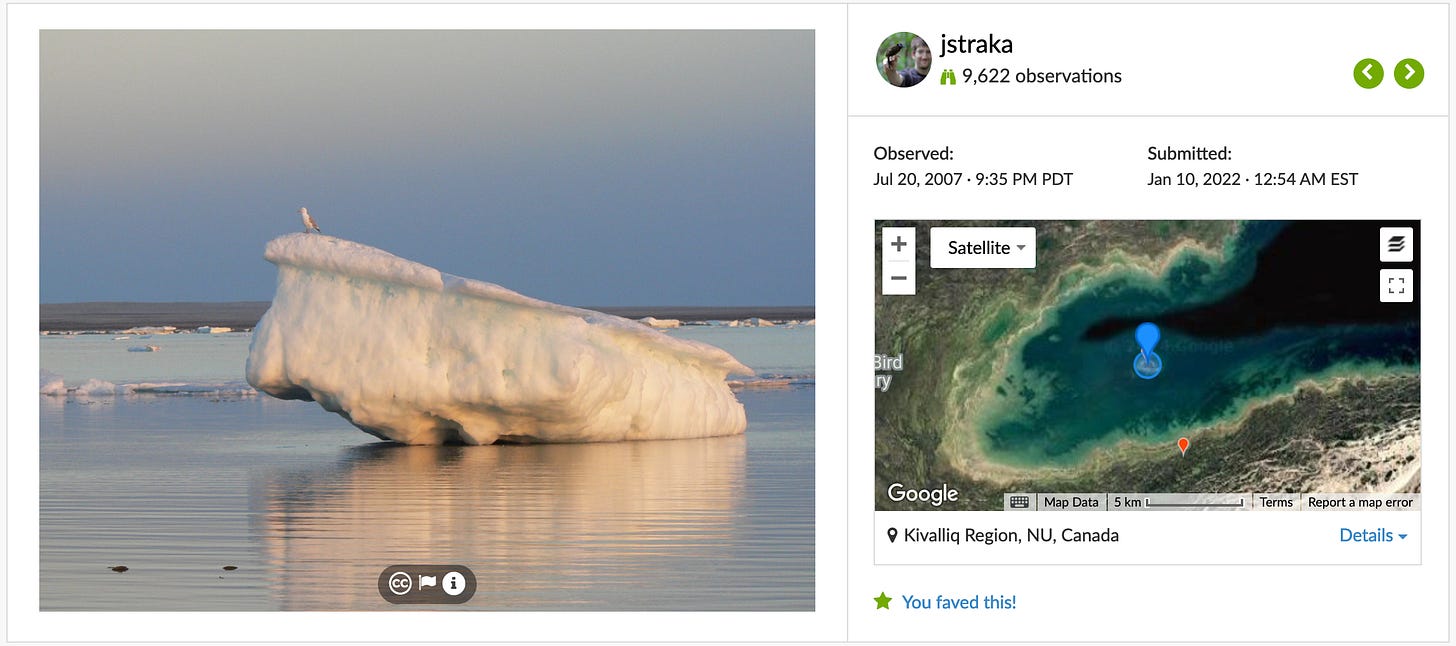

Herring Gull, Larus argentatus/smithsonianus

Kivalliq Region, Nunavut

July 20, 2007, 9:35 p.m.

It’s cold up there in Nunavut, I imagine. On the Switzerland-sized island of Shugliaq (Southampton Island), July 20 is the warmest day of the year, recording an average high of 58 degrees Fahrenheit. Still, it’s probably also cold up there on top of that iceberg where an American Herring Gull has placed its pink feet.

Its black primaries and silver mantle indicate that it’s an adult—at least four years old. Maybe it has chicks nearby, and it’s eyeing the frigid glassy water below for krill to bring back to a mossy nest. Maybe it’s keeping an eye out for prowling Gyrfalcons. Maybe, so to speak, it’s just chilling.

It’s half past nine. The sun doesn’t set for another 40 minutes. The iceberg glows.

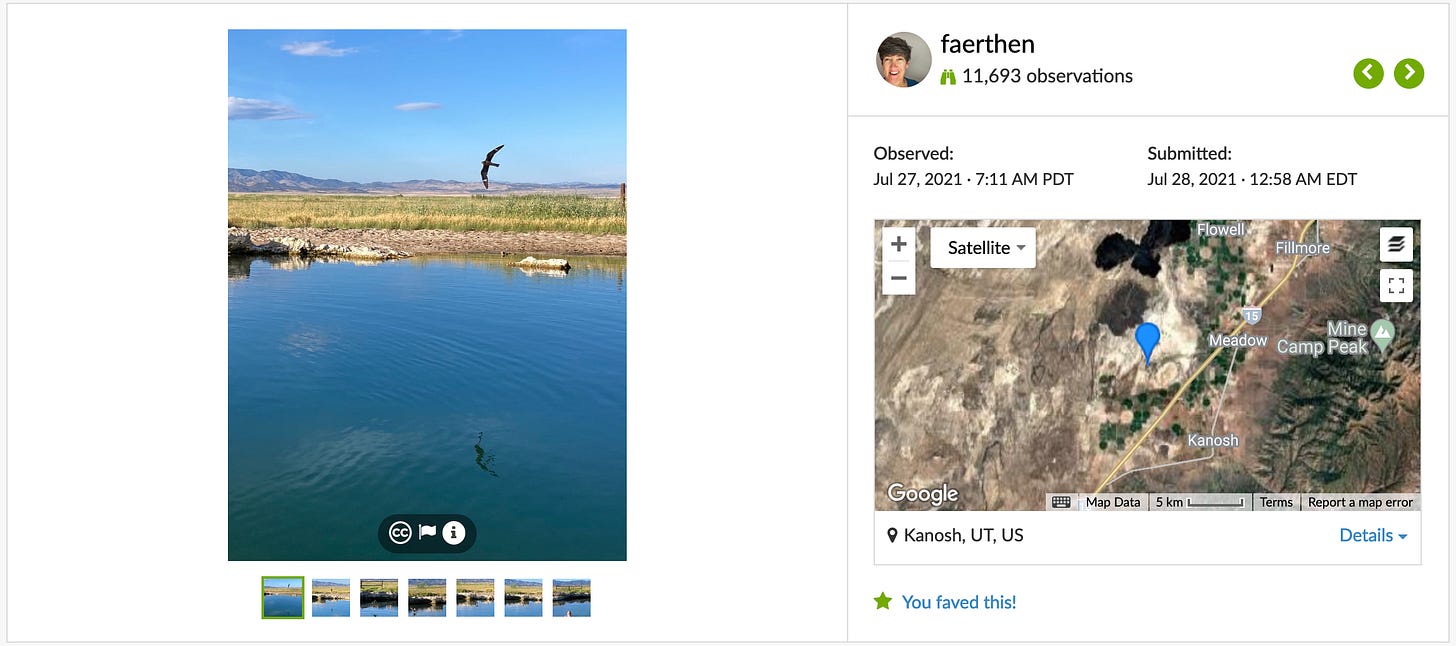

Common Nighthawk, Chordeiles minor

Millard County, Utah

July 27, 2021, 7:11 a.m.

Beneath Meadow, Utah, the Black Rock Desert volcanic field warms underground waters. Three small hot springs well up just outside of town in deep pools ringed by craggy white rock. I imagine that warm, still water in the middle of a desert might draw bugs, and in Utah in summer, bugs draw nighthawks.

Common Nighthawk is a bird made of quick. Their wingbeats come in erratic pulses, following no pattern intelligible by the human brain. A nighthawk’s speed and trajectory is governed by instincts only a nighthawk can perceive.

In July 2017 a local birder reported 20 Common Nighthawks while swimming in the “hot pots” one evening. In this iNaturalist observation from the morning of July 27, 2021, we see one swooping above the water, hinging open its alien maw to scoop prey from the air.

“Bird was not shy!” the observer, Faerthen Felix, remarks, and in the last image we can see what she means: The bird banks over the pool not far behind a white-bearded man floating with only his bald head above the water.

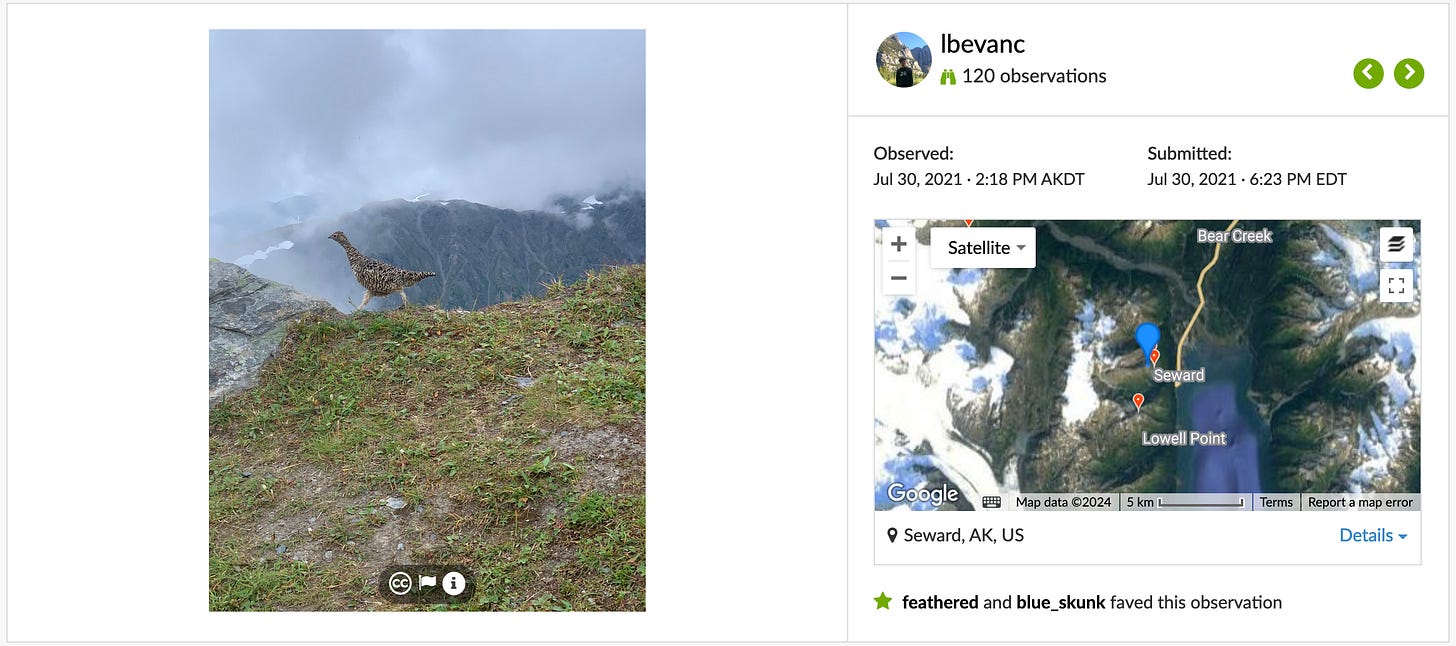

Rock Ptarmigan, Lagopus muta

Kenai Peninsula Borough, Alaska

July 30, 2021, 2:18 p.m.

Just about 3,000 feet above Resurrection Bay, a Rock Ptarmigan ptrots on ptip-ptoe along the ptop of an Alaskan ridge crest. The scientific name for the ptarmigan genus, Lagopus, refers to the rabbitlike softness of their feathered feet; I see them as a sort of alpine pigeon chicken.

This spot, Race Point, is so named for the annual five-kilometer Mount Marathon race that takes runners starting in downtown Seward, Alaska, up a steep slope of loose shale and back down the mountain again. Ptarmigans will move up and down the slope, too—some migrate from higher to lower elevations in the winter instead of from north to south.

Rock Ptarmigan is described as the “quintessential arctic bird” in its Birds of the World entry. I’m struck by this one’s adorable urgency—no time to dawdle, there’s a short summer to make the most of.

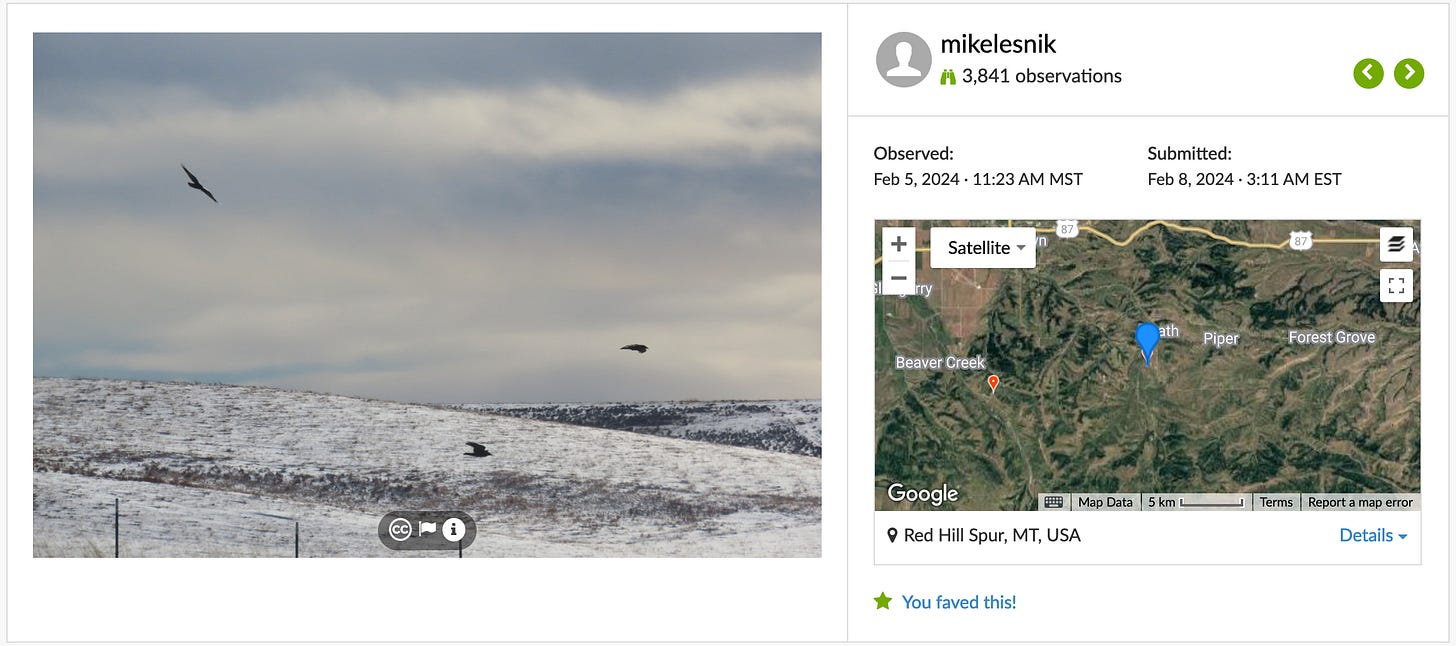

Common Raven, Corvus corax

Fergus County, Montana

Feb. 5, 2024, 11:23 a.m.

Three feathered missiles, absorbing all light against their wintry surroundings, carve the wind currents that course through the northern foothills of the Big Snowy Mountains, an island range in the middle of Montana (on a map, near the second “A” in the name of the state). The observer, Mike Lesnik, wrote that these Common Ravens are playing on the orographic wind lifted up by the ridge.

Play is rare in birds, but as Jennifer Ackerman describes in The Genius of Birds, we’re learning more and more about how play activities reflect avian intelligence. She writes that “play both requires intelligence and structures it”—a bird needs to be smart to have fun, but having fun develops the brain structures that reinforce being smart.

Black Scoter, Melanitta americana

Fort Smith Region, Northwest Territories

July 28, 2016

A female Black Scoter trails six chicks behind her, each one a miniature fuzzy carbon copy of its mother: soft chocolate brown, a pale cheek, a stubby dark bill, and a wary black eye shining in the taiga sun. It’s late July 2016 in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

Uncountably numerous small lakes are cast across the grassy landscape of low rocky hills. Nearby lie the ruins of Fort Enterprise, established by John Franklin during an English overland expedition of the Canadian Arctic (Franklin would later die searching for the Northwest Passage with the HMS Erebus and Terror).

Here in New York I know scoters as ducks of churning winter seas, but in the summer of the Canadian far north, they raise their young in the low grasses and fresh waters.

Merlin, Falco columbarius

Bannock County, Idaho

Sept. 19, 2021, 5:32 p.m.

A sunbeam striking through turbulent clouds points a bird atop a split-log fencepost. It’s a little falcon, so little that I thought it was a kestrel when the images were posted in July 2022, but it’s a Merlin: backlit, but we can make out the barred sandy back of the species’ prairie race, and a mostly black tail with a white terminal band.

The bird glances left in the first photo, then in the second photo swivels its head to stare over its left shoulder, eyes locked on the photographer. A Merlin will take any opportunity to choose violence. Pete Dunne writes in Hawks in Flight that a Merlin’s territory is wherever it happens to find itself. This one’s territory is at present an expanse of southeast Idaho grassland in the Snake River valley.

Its dominion is sagebrush laden with golden blossoms, shocks of corn-colored grass stalks; it rules tyrant over those—larks, sparrows, mice, lizards—who scurry beneath.

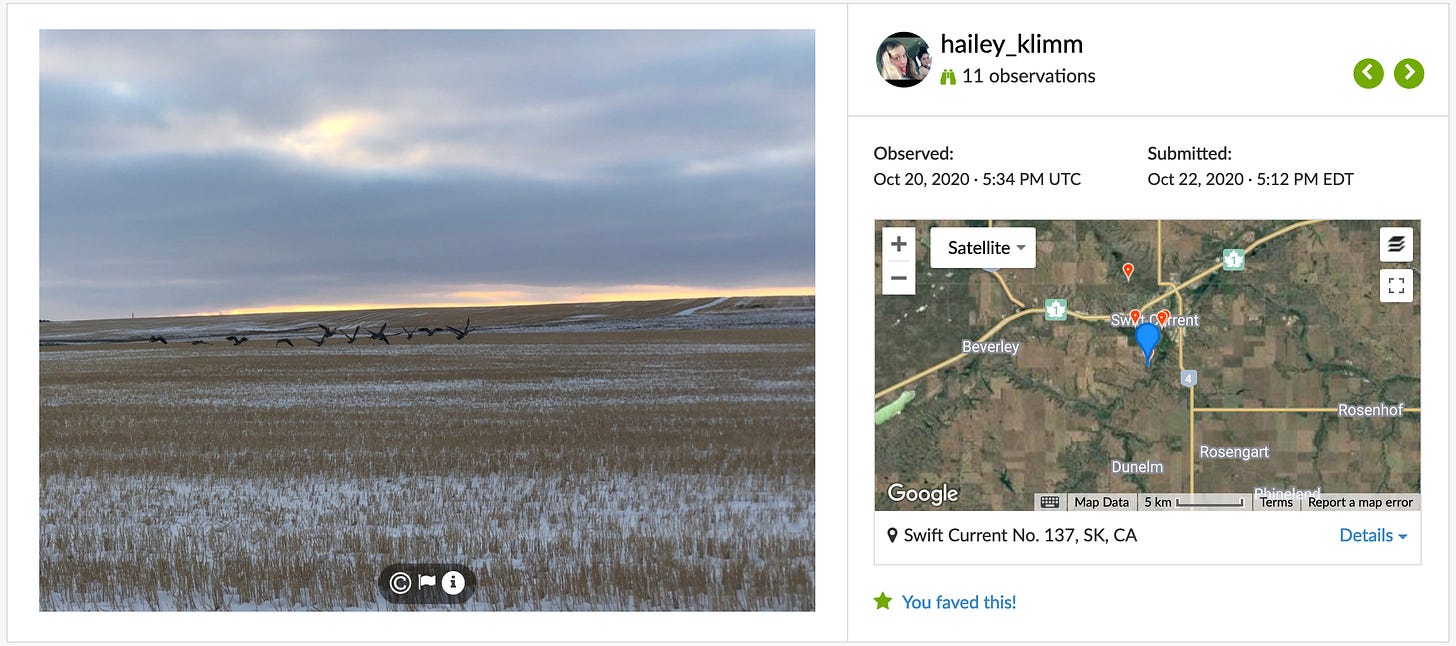

Canada Goose, Branta canadensis

Swift Current Rural Municipality, Saskatchewan

Oct. 20, 2020, 5:34 p.m.

On Oct. 20, 2020, I was in a Brooklyn apartment sheltering from the delta variant, making plans to vote early before Election Day in a couple weeks and thinking of what we could do to somehow have fun while staying in on Halloween night. That evening, these fourteen Canada Geese were flapping over snowy fields of stubbled wheat in Saskatchewan. I’ve never known a skein of geese taking off to be a calm scene, but in the photo, we see a cold peace.

They’re heading toward the setting sun, a cold orange glow around the clouds’ ashen shoals. An oxbow of Swift Current Creek lies in that direction. Maybe they’re on their way there to roost, sheltering among the grasses nourished by the memory of a river.

Things have been worse than this before and things will be just as bad again. Whether things will get better after that is of no concern to geese.

This was really fun!

Beautiful thank you!!!