It’s a Bird— It’s a Plane— Oh No

A deep dive into the data behind American aviation’s grisly bird strike problem.

A note: This piece contains detailed discussion of bird death.

Birders often acclimate themselves to the knowledge that birds routinely die in all sorts of awful ways out there in nature. Even crueler than nature, among whose subjects few find an easy death, is the collision between nature and a mechanized industrial settler society. In the lower part of the sky we have placed hard objects—reflective windows, wind turbine blades, aircraft—that birds cannot avoid, either because they are invisible to their eyes or move faster than they can account for.

A year and a half ago I came across1 an exceptional dataset: the Federal Aviation Administration’s National Wildlife Strike Database, which, in 2024 alone, recorded reports of 155 American Barn Owls, 43 Scissor-tailed Flycatchers, and one Black Swift struck by aircraft.

“I saw something flash in front of us and a loud thud on the front of the plane,” one commercial pilot reported from an April 26 strike on approach to Corpus Christi, Texas.

“There was a bunch of birds, probably 10-15. Tried to avoid by going around but that was inevitable,” wrote a Cessna pilot in Brownwood, Texas, on September 8. “Hit three on the left wing. No damage to the aircraft. There was blood and feathers on the fuselage so I will believe the birds [got] striked well.”

In these high-velocity impacts, “snarge”—the “putrid mix of blood, guts, feathers, muscle, and tissue,” as Audubon put it in 2020—is often all that’s left. As in a portmanteau of “snot” and “garbage.” As in, “all that was left was a smear of snarge and feathers,” from Burlington, Vermont, on May 9.

In these cases, the Smithsonian Institute’s Feather Identification Lab, whose work is described in the 2020 Audubon profile of Roxie Laybourne, works to identify the species from whatever remains are scraped off the plane and sent to Washington. Their identifications, along with identifications made by staff biologists at airports around the country, shade ornithological depth into the massive database of wildlife strike reports.

At the time of writing, the Federal Aviation Administration’s National Wildlife Strike Database is available at wildlife.faa.gov. The data I used, as downloaded on April 10, 2025, and the code I wrote to analyze it are available for viewing and download on my GitHub.

The figures and trends I describe here are derived from incidents that were first detected and then voluntarily reported. Many bird strikes must go undetected, and reporting them is common but not compulsory, so the data here sketch a thorough but imperfect outline of the true extent of wildlife-related aviation incidents in this country. I imagine the true numbers to be significantly higher.

2024 in review

The dataset is up to date into the second week of November (about the same as the timeframe that Spotify Wrapped uses), with enough incidents entered through the quiet month of December to sketch out the year’s trends. For the 2024 analysis, I’ll be using just the data from the 50 U.S. states and Washington, DC (there are some territorial and international reports).

by species

Four hundred and seventy-seven taxa were recorded in 16,209 incidents—an average of 44 each day. The vast majority—the exception being 940 incidents involving 71 species of mammals and reptiles2—are about 400 taxa of birds.

Many are identified to the species level, like a Glaucous Gull—a rare species in Wilmington, North Carolina—that was struck with gruesome intensity on Oct. 27 (“bird intestines came out”). Others are left at the genus, family, or order level, like an intriguing July 11 report from Dallas Love Field of “parakeets,” presumably from a population of escapees.

Often, though, the remains were not or could not be identified. Sometimes, the remains could only be identified, even by the experts, to the genus or family level. Of the 10 taxa most frequently listed in the database, three are some kind of unknown bird.

Excluding non-avians and unknown taxa, 353 bird species were identified from collisions with aircraft in 2024. Poring through these reports yields some rarities that birdwatchers never observed alive.

On the 2024 species list appear two Hawaiian endemics of conservation concern: a Nene/Hawaiian Goose (population <4,000) at Kauai’s Lihue Airport on April 15, and two Koloa/Hawaiian Duck (population <2,000) at Honolulu on August 31.

Yellow Rail is uncommon, highly local, and hard to find, so it makes sense that there are no eBird records of the species in areas throughout its migratory corridor in the Midwest. In the apparent absence of any live observations, the first Vanderburgh County, Indiana, record of Yellow Rail seems to be represented by a nocturnally migrating individual struck on Sept. 29 on approach to the Evansville airport.

At 6 a.m. on Oct. 10, a Sabine’s Gull was struck on takeoff from Medford, Oregon, 80 miles from the Pacific. It’s so unusual for this pelagic seagull to end up inland, let alone near an airport, that this was the first and so far only one to be recorded in the database. As gull expert Amar Ayyash observed on the Anything Larus blog, fall 2024 was a record-breaking season for inland Sabine’s Gull sightings. This individual, though, seems to have gone undetected until it was violently detected by a Portland-bound Embraer 170.

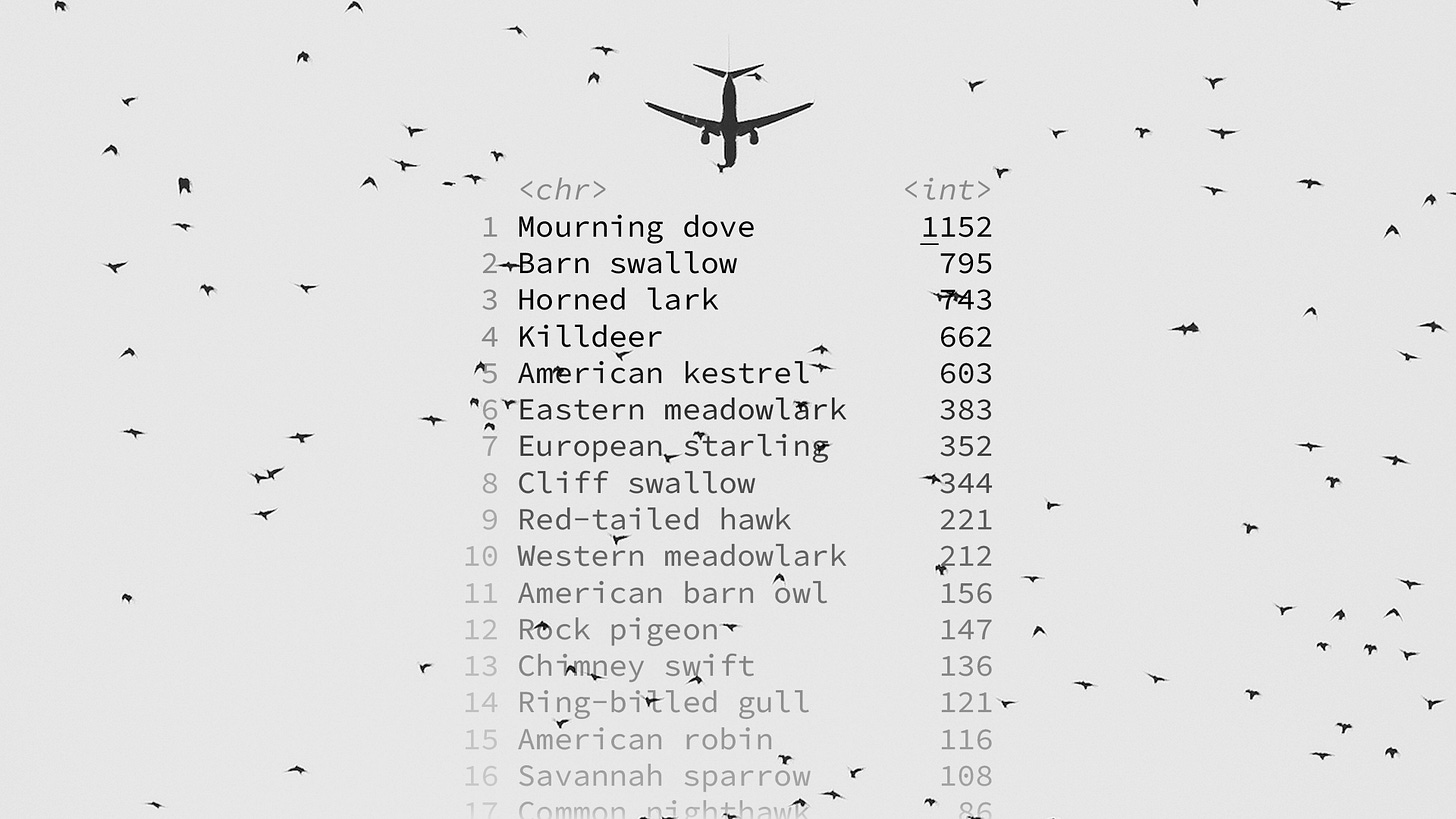

The commonly struck species, on the other hand, are generalists that enjoy grassland habitats like those that surround airport runways.

With 1,152 incidents, the abundant and widespread Mourning Dove was struck more than any other species in 2024. More were reported from Dallas/Fort Worth International than any other airport, while they made up a greater percentage of the total at Phoenix-Mesa Gateway.

by location

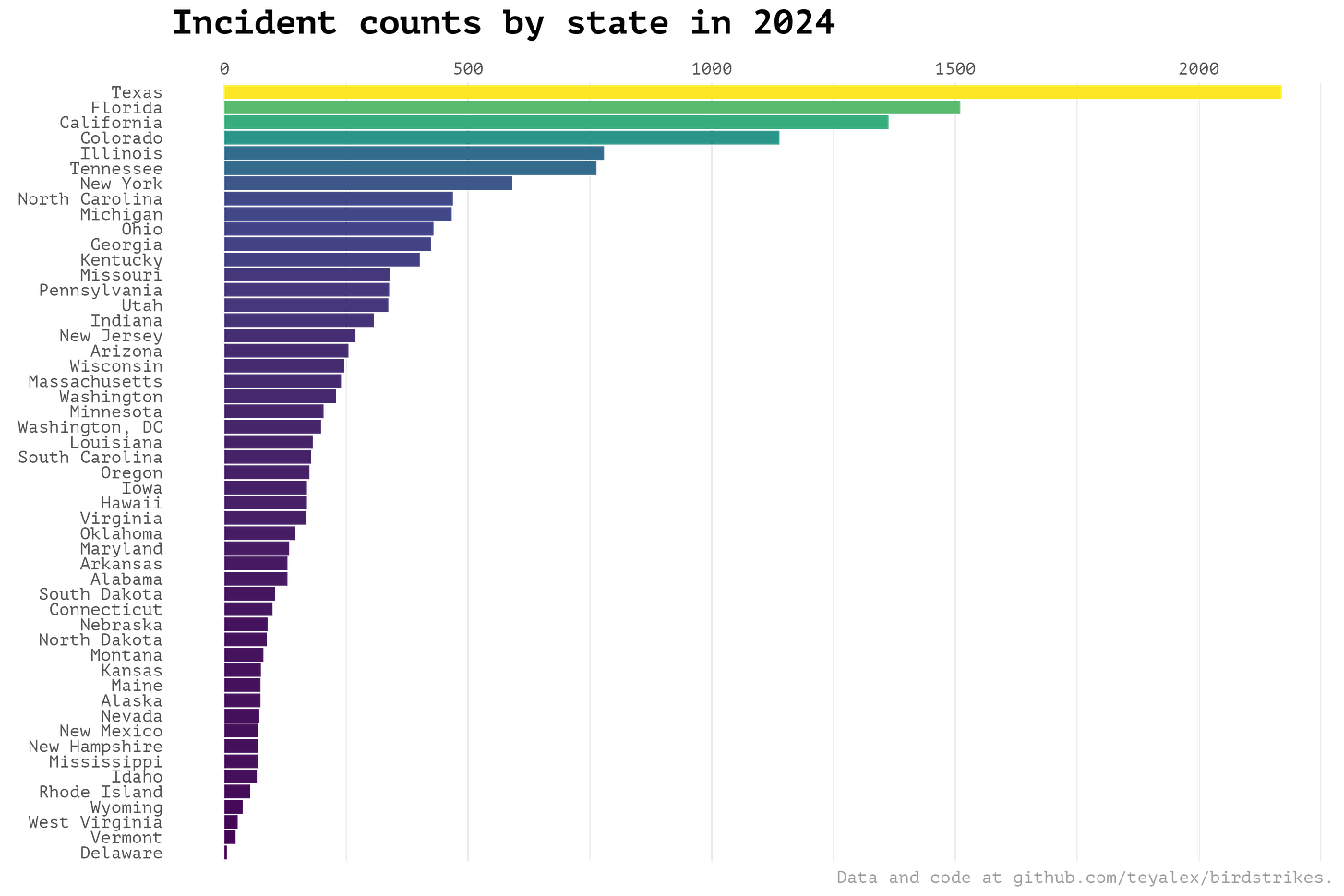

With 2,170 incidents, Texas reported by far the most incidents of any state in 2024. Florida (1,510) and California (1,363), the other two of the three most populous states, followed.

In fourth is Colorado, despite being No. 21 in population, because of the Denver airport’s outlier status. As in most years, Denver International had the most wildlife strikes of any airport in the country last year. With 828 incidents, the United, Southwest, and Frontier hub stands ahead of Dallas/Fort Worth International (479) and Chicago O’Hare (478) in second and third.

It’s very possible that this is just because they report more rigorously than other airports, but it would also make sense if Denver actually did have more wildlife strikes. With six runways, including one three-mile-long runway that’s the longest in North America, Denver International is an extraordinarily large airport, measuring 52.4 square miles. Not only is it the world’s largest airport by area, it’s also one of the busiest airport in the country. Its sprawling layout creates many acres of potential habitat between the runways, and it lies adjacent to croplands and grasslands, including the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge that separates it from metropolitan Denver.

The airport makes substantial efforts to detect, deter, and disperse birds and other wildlife with measures like mowing grasses and draining water. Perhaps Denver’s top species is such an outlier because, while effective at reducing habitat quality for most birds, those practices inadvertently amount to managing an area for the benefit of the Horned Lark (343 strikes).

The full list features a few Western specialties—one each of Calliope Hummingbird, Green-tailed Towhee, Lapland Longspur, and Thick-billed Longspur. Not all the incidents involved birds, and not all involved collisions: On October 29, a Southwest 737 arriving from Albuquerque “encountered a large pack of raccoons crossing the runway,” the remarks state. “The raccoons went around/underneath the aircraft,” apparently unharmed; no aircraft damage or animal remains were found.

Especially at the country’s busiest airports, wildlife strikes happen regularly. But they are infrequent enough that they are more of a risk for individual aviators to consider than a threat to avian populations. An FAA list of about 80 major airports accounts (by my calculations) for roughly three-quarters of the flights in the U.S.; in this set, about 0.2% of flights—roughly one in every 461—reported a wildlife strike in 2024.3

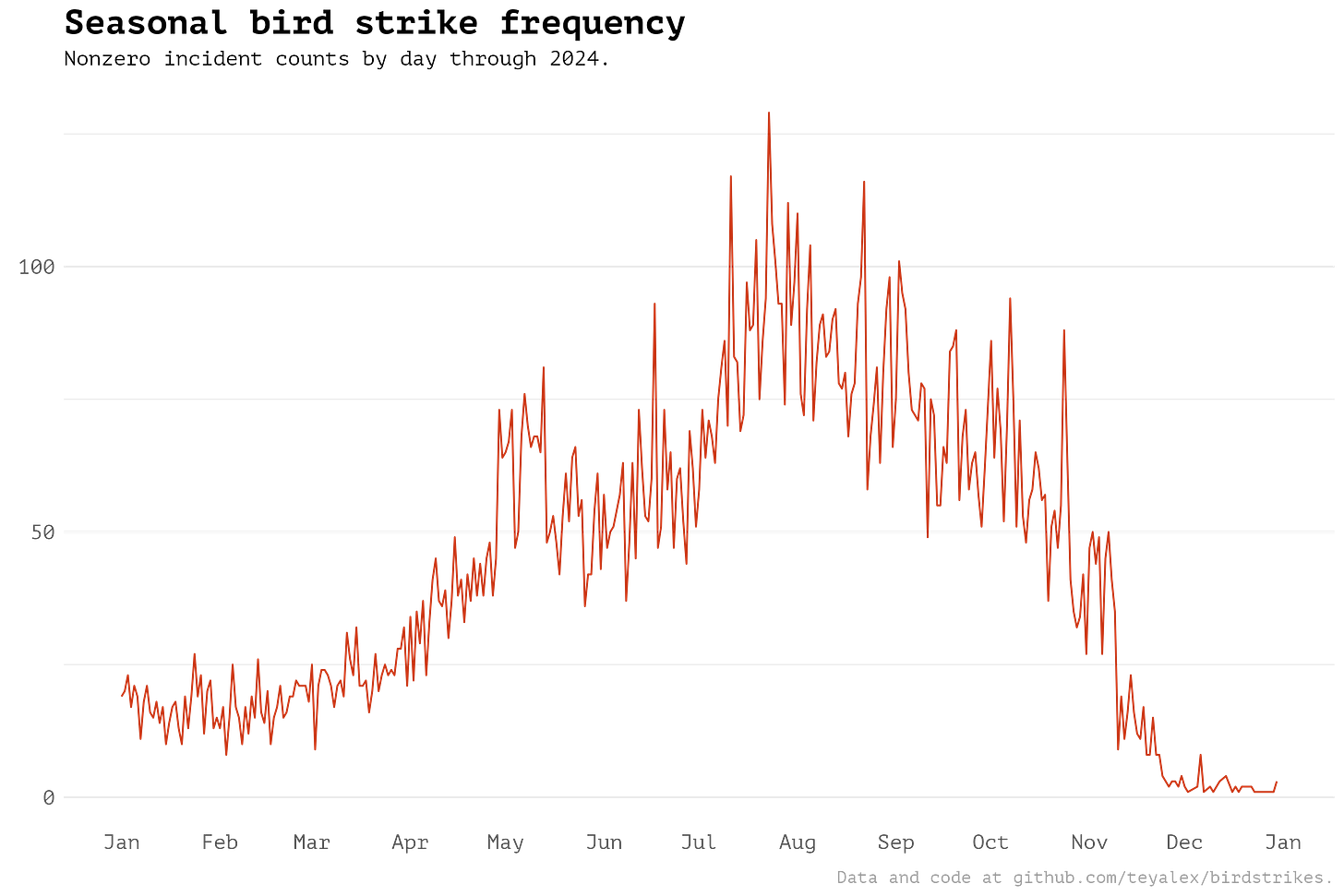

The heaviest time of year for bird strikes is late summer, as birds young and old disperse from the breeding grounds, followed by the long tail of the southward migration. The winter low (in this case partially due to incomplete data) builds up to small, sharp spike during mid-May spring migration before a lull in early summer.

The historical data

The entire database contains records from:

317,105 total incidents

2,701 total airports

929 total taxa

699 bird species

56 genus (or higher) -level bird IDs

174 non-bird taxa

Turning to all the complete years recorded (1990 through 2023), we see the same seasonal trends.

The higher counts described by the redder lines, which represent more recent years, show how incidents have become both more frequent and better reported as air travel has increased over time. Aggregating these counts by month produces a clearer picture of the central tendency and variance of the seasonal trend.

Thirty of these taxa have been struck 1,000 times or more.

Perhaps because nocturnal bird activity often involves higher-altitude migration instead of lower-altitude foraging, or perhaps because a bird flashing in the plane’s lights at night is more likely to be noticed by a pilot, or simply perhaps because many airports do not perform takeoffs or landings at night, nighttime bird strikes tended to be at a significantly higher altitude than daytime ones.

And while the biggest airports file the most reports, incidents have been recorded throughout the country.

Looking closer at the farther-flung locations reveals rarely seen portraits of bird life and bird death.

At Henderson Field on Midway Atoll, for instance, four-propeller Coast Guard C-130 transport aircraft occasionally record collisions with the seabird species that breed there. Most of the reports involve Laysan Albatrosses, whose main nesting colony is on Midway, but Wedge-tailed Shearwaters, White Terns, Brown Noddies, and Bonin Petrels have all had grisly run-ins with C-130s.

“A second petrel was found neatly cut in two and the initial petrel lay on the ground from some type of trauma,” reads a report of a Bonin Petrel strike in March 2014. In October 2010, a pilot reported “seeing a [small] flock of about 5 birds just as he was touching down and thought he hit them all,” the report reads. “Only 1 carcass was found, a brown noddy cut clean in half by the propeller.”

Military aircraft at Midway once struck 300 to 400 Laysan Albatrosses a year. These days, flights during nesting season take off and land at night to reduce the chance that seabirds will cross their flight paths. Still, there are lots of ground-nesting albatross in the area. Google Street View imagery from June 2012 shows numerous young albatrosses sitting on the tarmac; in 2023, a C-130 turning around at the end of the runway ran over a Laysan Albatross chick.

A quadcopter drone examining crop damage in Tennessee in 2022 was brought down by a swift- or swallow-like bird. Briefly turning the tables, a Bald Eagle attacked a similar drone surveying shoreline erosion along Green Bay in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in 2020, perhaps mistaking it for a gull.

Bald Eagles, as it happens, have the bad luck of being large, long-winged, widespread soaring birds that share habitat preferences (open areas near water) with airports. Sometimes, they even have the bad luck to survive a collision with a plane. In these cases, they typically die from or are euthanized for their injuries—often broken or severed wings—but at Washington’s Dulles airport, one eagle that was dealt a glancing blow by an Airbus A320 in October 2010 went on to recover at a wildlife center. A strike in South Dakota in July 2023 was more typical, resulting in “multiple pieces of the bald eagle on the runway, spread out for about 200 yards.”

The rest of the reports under “drone” come from a fleet of MQ-9 Predator B drones operated by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. They fly out of Libby Army Airfield at the municipal airport in Sierra Vista, a birding hotspot in southeast Arizona—the drones’ runway lies less than 10 miles from Ramsey Canyon and less than 20 miles from the Mexican border. Along with a handful of unidentified birds and bats, the MQ-9s have been reported striking three Horned Larks and one each of Northern House Wren, White-crowned Sparrow, and Great Horned Owl.

Continuing down the “aircraft” column leads us to one entry under “space shuttle.” The shuttles used to launch and land at the NASA facility on Merritt Island at Cape Canaveral, the former home of the now-extinct Dusky Seaside Sparrow. On July 26, 2005, Discovery was set to embark on the program’s first mission since the Columbia disaster. A YouTube video shows a small flock of Turkey Vultures soaring above the launchpad as the rockets fired. As the shuttle lifted off, one bird collided with the nose of the external fuel tank and tumbled into the blast of the rockets. “No remains found,” the FAA report’s remarks note. “Bird thought to have been vaporized by rocket plumes.” Though a bird strike never damaged a space shuttle, its location in a Florida wildlife refuge meant it was always a risk. Additional measures have since been taken to detect and deter Turkey Vultures in particular.

Cape Canaveral was also the site of the only fighter jet bird strike recorded in the database when an F/A-18 struck a Short-tailed Hawk in August 2017 (Navy and Air Force jets that get taken down by birds don’t seem to be recorded here). Between September 10 and 13, 2024, T-38 training jets associated with NASA’s astronaut training flights in Houston accounted for three of the year’s eight Buff-breasted Sandpiper strikes. In central Texas in February 2008, a T-38A struck at least two Sandhill Cranes in a flock flying 4,000 feet above ground level.

rare birds

On Halloween 2007, a flock of five endangered Whooping Cranes—the species’ wild population would stand at 266 by the end of the year—was migrating south from their ancestral breeding grounds in Wisconsin. A juvenile in the flock named DAR 41-07 (nicknamed “Rivet”) had been reared in captivity and released in the fall to follow adult birds on the southward migration path. But cranes of all species like short grasslands and can be found around airports; that evening around 8 p.m., a Cessna Citation II business jet landing at the Dane County airport struck and killed 41-07 on the runway.

The owner reported $75,953 in repair costs—“had to rent a flap while repairs were being made,” they wrote.

Another kind of rare bird—a vagrant, not an endangered species—was hit by a Delta 737 around Boston’s Logan airport in September 2023. As the Smithsonian ID noted, Sharp-tailed Sandpiper “is a rare but regular vagrant to the eastern US” broadly. That individual, though, would have been the first record for Boston’s Suffolk County and the fifth record for Massachusetts. (An Upland Sandpiper recorded at Maui’s Kahalui Airport back in March 2000 would have been Hawaii’s first record of the species if the report were any more detailed than “down & blood streaks on side of nose” of a DC-9.)

Sometimes, an animal’s remains were noticed far from where they were struck—Asian bats carried over from Delhi, a European swift and finch carried over from Amsterdam, bits of various songbirds carried around the United States like bugs on the windshield during a cross-country road trip. In one extreme case, a Mugimaki Flycatcher scraped off a Hawaiian Air A330 in Seattle must have been struck “several legs prior to discovery,” while the plane was in Seoul, the report surmises.

The most remarkable story of a rare bird struck by a plane, though, is surely that of the Western Marsh-Harrier that visited the Northeast in 2022. It was discovered in Maine in late August, then disappeared before being refound in New Jersey on Nov. 8. Many observers sought the bird the next day, but it was only seen for an hour and a half before vanishing until Nov. 12. That day, the last birder to see it alive provided a thorough account of its detection and observation in his eBird checklist, and noted that the bird was “simply striking,” entirely unlike any North American raptor. Noting favorable migration conditions in the coming days, he speculated that the bird might move southward. Seven days later and 13 miles to the southeast, a United Airlines 737 taking off from Newark Liberty International Airport turned the second U.S. record of Western Marsh-Harrier into the first U.S. specimen.4

state birds

Uncommon birds have symbolic importance for bird enthusiasts, but certain common birds hold a symbolic importance for the public. Of the 67 official birds of each of the 50 U.S. states and Washington, DC (some have state game birds or waterfowl in addition to their state birds), 46 have been struck in their states.5 Forty states have had a strike on at least one of their official birds.

banded birds

Another way that a bird can be significant—as an individual, not as a state symbol or population member—is to be banded, to have a small aluminum ring placed around its leg so that if it is recovered, dead or alive, biologists can retrace to the place it came from its story and with it the story of its species.

Six hundred and seven banded birds representing 48 species lie in the database. Most are raptors, which are commonly banded as nestlings: 175 Peregrine Falcons, 133 Red-tailed Hawks, and 93 American Kestrels lead off the tally. Several of the falcons were struck while carrying prey—a sandpiper here, a songbird there. Some of the comments evoke the care given to individual birds that met brutal ends against airplanes.

A Common Nighthawk struck in Cleveland in August 2019 had been “an orphan, hand-reared to releasable age” near a nature reserve about three miles away.”

“My son-in-law is a crop duster,” reads a September 2016 report of a banded American Goldfinch. “He found the bird smashed into his plane. He tore the leg off what was left of the bird and brought me the leg with the tag on it.”

In 2017, a Red-tailed Hawk was trapped at New York’s Kennedy airport in 2017 to be relocated 45 miles away to the safety of Harriman State Park and its ancient mountains along the Hudson River. By early March 2020, though, it had found its way back to its death at JFK.

The toll

In terms of human casualties, 374 injuries and 12 fatalities are reported in the database, although far more have been recorded elsewhere. The 1960 crash that launched the subfield of forensic ornithology killed more than 60 people in Boston; more than 250 died from bird strikes worldwide between 1988 and 2016.

Of the pilots whose crashes were reported to the FAA database, one recovered the remains of the hawk he hit as a souvenir of his crash into a tomato field. Another was “covered with blood and duck remains.”

The No. 1 species associated with causalities was White-tailed Deer. In January 2001, a Learjet belonging to Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones struck two deer and overran the runway upon landing in Alabama, severely injuring the two pilots onboard and dealing nearly $17 million of inflation-adjusted damage. It was the plane’s second run-in with deer.

Second on the list of casualty-associated species—and the one that gets the most blame, including, sometimes, culls within several miles of an airport—is Canada Goose. In the famous Miracle on the Hudson, when Chesley “Captain Sully” Sullenberger piloted an Airbus A320 to a water landing, a flock of Canada Geese dealt $53 million of damage. The Concorde also once hit a flock of geese in New York while landing at the Kennedy airport for $19 million of damage.

High-profile crashes like these have defined the narrative of bird strikes, but numerous smaller incidents add up to mounting costs and constant risk. The FAA estimates that repairs surpass $900 million annually, a fraction of which are recorded in the database.

A wildlife strike is more likely to result in severe damage for small planes and helicopters than it is for passenger airliners and private jets. In Hawaii, three people have been reported injured in collisions between sightseeing helicopters and tropicbirds alone (“never saw bird,” one wrote; “sounded like a cannon ball coming thru”). Two people sustained minor injuries in November 2023 when a medical transport helicopter intersected a flock of Hooded Mergansers in Minnesota. During a 1996 aircraft-assisted coyote hunt in North Dakota, men on the ground inadvertently flushed 30 to 40 Sharp-tailed Grouse up toward a Piper Super Cub. One grouse took out the left half of the windshield, dealing minor broken-glass-associated injuries to the two passengers. In March 2003, a single-engine Beechcraft Bonanza was destroyed in the Florida Keys, injuring two, after the pilot pulled up abruptly on takeoff to avoid a dog on the runway.

Aircraft strikes are not likely to have an impact on most bird populations. But in some populations of conservation concern, like Koloa/Hawaiian Duck or Whooping Crane, every individual counts. And how could we put into words or figures the importance of a single vagrant individual like the Western Marsh-Harrier? Anthony Ferino wrote on eBird that the wandering hawk “seemed like it had potential to remain in North America for years, stamping its passport in who-knows-how-many different states.”

Still, while 317,000 incidents in 34 years is a lot of dead birds, it is orders of magnitude apart from the number we’ve lost to other human activities. Even within the category of vehicle collisions, cars kill tens to hundreds of millions of birds annually. Window strikes kill over one billion, and cats kill billions more.

More difficult to enumerate is the avian death toll from aviation’s contribution to anthropogenic climate change. Cutting down on air travel would—in addition to sparing a number of individual birds from death by plane strike—reduce carbon emissions that threaten global bird populations on a much larger scale.

Airport construction has also destroyed critical marsh habitats—the infill of much of Idlewild Marsh for New York’s JFK airport “obliterated the finest known colony” of Saltmarsh Sparrows on Long Island.6 That species is now threatened with extinction as its low-lying nests are swallowed by rising tides after decades of marsh destruction, making the few habitats remaining all the more valuable.

For now, though, at least none are recorded in the National Wildlife Strike Database as having been struck by a plane.

Thanks to Meredith Broussard of NYU Journalism, who introduced me to this data set and to thinking journalistically about data. Thanks also to Matthew Hayek and Docker Clark of NYU Environmental Studies, who taught me R and advised me on early versions of this project.

Some large mammals, like bears, seals, and moose, are reported in the database not because of strikes but because they delayed aircraft that had to wait for them to get off the runway.

Data from the ASPM 82 airports recorded in the FAA’s Aviation System Performance Metrics and the Bureau of Transportation Statistics’ TransStats. A few airports with no data were excluded from this analysis.

Index No. 1348054. You can read more about this remarkable episode in the Birdwatching Daily article about the sighting and the Smithsonian’s paper about the specimen identification.

Since 2017, Oregon has both an official raptor (Osprey) and official songbird (Western Meadowlark); both are included here. Pennsylvania only has a state game bird (Ruffed Grouse, zero incidents). I checked for Guam (ko'ko'/Guam Rail), the Northern Mariana Islands (Mariana Fruit-Dove), Puerto Rico (unofficially Puerto Rican Spindalis), and the U.S. Virgin Islands (Bananaquit), but none had any strikes of their official birds. American Samoa does not have an official bird. In Wisconsin, the Mourning Dove is the state symbol of peace, which I felt didn’t fit the spirit of official birds. If included, it would top the list with 164 incidents.

Elliott, John J. “Sharp-Tailed and Seaside Sparrows on Long Island, New York.” The Kingbird 12, no. 3–4 (1962): 115–23.