Split

What can I count on?

This is an essay that is nominally about the Clapper Rail.

I say “nominally” not only because I am writing about this bird as a way of trying to write about something else, but also because I am writing about this bird’s nominal characteristics. I am interested in naming, classification, specific statuses at specific points in time.

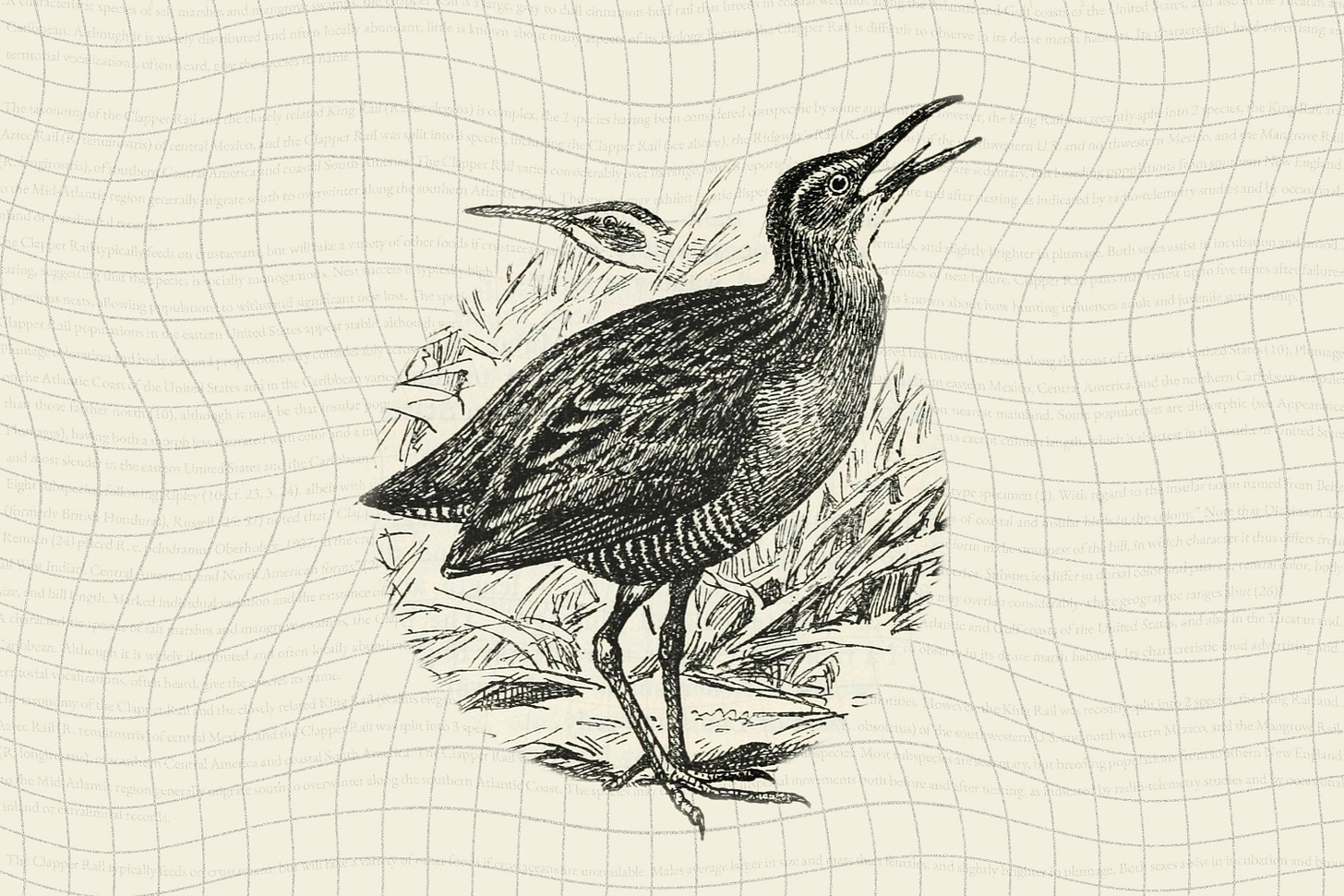

If I were writing this essay ten years ago, for example, I wouldn’t have needed to clarify further that I am in fact writing about two species of rails. In 2013, Clapper Rail was just Clapper Rail, an elusive bird of tidal marshes that resembles a combination of a chicken and a sandpiper.

But these days, my hometown rail is considered a different species entirely: Ridgway’s Rail. More precisely, it is the San Francisco Bay subspecies; two other subspecies are present in southern California, one along the coast and another along the lower Colorado River.

Seldom seen, it is typically detected by its vocalizations, which are often described as grating, harsh, or unmusical. The great ornithologist Robert Ridgway, for whom the species is named, described rail calls as “remarkably loud, often discordant.”

The Clapper Rail that I could find at the marshes where I learned to look at birds in the 2000s was then considered the San Francisco Bay variant of the California Clapper Rail, a regional subspecies. That was how it was presented on the signs at the preserves, in the discussions at Christmas Bird Counts, on every checklist I could find. The taxonomic grid, and the rail’s place in it, seemed to me at the time something as rigid as timekeeping.

The group of rails surrounding Clapper Rail and the related King Rail, however, and questions of which ones qualify as full species, “have vexed systematists and taxonomists for decades,” William Eddleman and Courtney Conway write in the Birds of the World accounts for Ridgway’s and Clapper Rails.

In 2014, Clapper Rail was divided into three species. In the taxonomic reshuffling, the “original” Clapper Rail back east became Rallus crepitans, while the newly minted Mangrove Rail of South America got to keep the scientific name R. longirostrus. And our San Francisco Bay specialty and a few closely related subspecies were together granted full species status as Ridgway’s Rail, R. obsoletus. Genetic analysis has allowed scientists to be about as sure of this as they can be.

These matters are the jurisdiction of the American Ornithologists’ Union, which announces its decisions in annual updates to its checklist. That list curates the set of North American bird species “that the bird research community agrees are real,” as my friend Ryan put it in a Substack post about another taxonomic decision.

When ornithologists decide that one species should really be thought of as two or more, this is called a split. When it goes the other way, it’s called a lump.

The ramifications of splits and lumps are not only scientific. Birdwatchers tend to care about keeping track of the number of species they’ve seen, a figure called a life list. Depending on how seriously one takes the counting, it can be pleasing to gain a species from a split or irksome to lose one to a lump.

In my childhood bedroom, I read field guides and birding memoirs and fantasized about making a name for myself in the bird world with my list. A respectable life list in the ABA Area, the preeminent listing jurisdiction defined by the American Birding Association, could put me on the map, I thought.

My life list signified more to me than just a measure of how much birding I had done. Some birders primarily keep lists as a means of competition or prestige. But for me, the list framed the natural world for my childhood eyes. Here are the birds I have seen; here are the birds I have yet to see. Between the two groups, every living thing—at least the ones I cared about—could be cataloged, tabulated, understood.

Rails fascinated me as a child. I thought of them as elusive, near-mythological marsh-dwellers, cryptic creatures that I would need luck to hear and divine intervention to see.

I spent afternoons laying on the carpet in my bedroom poring over the photographs and essays in Willliam Burt’s Rare and Elusive Birds of North America, a coffee-table volume given to me by a family friend. In the introduction, Burt describes the allure of the most unremarkable, difficult-to-find birds, including rails. “To those who know them they are creatures of irresistible appeal,” he writes. “It is the elusiveness, the inaccessibility, that fascinates.”

In the mid-1990s, the San Francisco Bay subspecies of Clapper Rail was elusive indeed: Its population was estimated to have declined to fewer than 300 individuals. A sizeable majority of the bird’s habitat had been destroyed over the course of the previous century. By 1959, about 80% of the salt marsh habitat in the southern part of San Francisco Bay proper had been repurposed for salt harvesting, agriculture, and industrial and residential development.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, human activity was already known to be a factor in the depletion of rail populations. Hunting preceded industry in engendering the bird’s decline. As early as 1927, Dudley Sargent De Groot wrote in The Condor that “there is no question but what we owe a good deal of the depletion of rail to these so-called sportsmen.”

De Groot himself noted that conservation concerns had been expressed in ornithological circles as early as 1894. The 1913 enactment of a federal law protecting migratory birds (this was followed by the enduring 1918 Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act) gave ornithologists cause for optimism, but De Groot remained alert to the rail’s plight.

He lists six “enemies” of the bird, chief among them “industry and the encroachments of civilization upon the few remaining haunts of our rail.” Hunters, invasive rats and mussels, egg collectors, and finally native predators follow. While his depiction of the rail is unflattering—he describes the “clownish and helpless flight” of “this pathetic marsh dweller,” De Groot is driven by an abiding affection for the bird, no matter how silly he finds it.

“Anyone who knows the Clapper Rail,” De Groot writes, “cannot help but love him.”

The species’s demography remains difficult to survey and not well understood, but today, populations are thought to have rebounded modestly thanks to habitat restoration. By re-establishing natural waterways, promoting tidal flow, and cultivating native plants, conservationists gave back to the rails pieces of the habitats in which they once thrived. Measures to curtail non-native predators like red foxes and feral cats have also helped the rails return.

Ridgway’s Rail, as it is now known, is frequently observed at places like the MLK Jr. Regional Shoreline in Oakland. Restoration efforts there have breached levees and removed bayfill to reshape the wetlands back toward their original marsh habitat. The endangered rail is one of the project’s species of special concern: “Listen for its chattering call, a sound once common in the Bay, and nearly lost,” a sign at the preserve reads.

At this location, at least, that call is once again common: Ridgway’s Rail is reported on about 59% of eBird checklists at the MLK Jr. Regional Shoreline hotspot. And within Arrowhead Marsh at the northern end of the preserve, the species is reported on just over 70% of checklists. In 2010, a birder at the marsh recorded 49 Ridgway’s Rails “climbing over vegetation over the entire ‘arrowhead’ area,” an “unforgettable day” that remains the record high count for the species in Alameda County.

Across the bay in Santa Clara County, the Palo Alto Baylands Nature Preserve provides its own haven for the threatened rails. That county’s record of 20 individuals was “not considered an unusual count at a high tide in 1979.”

While that tally hasn’t been matched there since, Palo Alto Baylands is still one of the most reliable spots around for Ridgway’s Rail. It was a favorite birding spot of mine as a child in the mid-2000s. (Whenever I’m visiting my nearby hometown, I still check the spot for rails.)

Less than a mile from US-101, the freeway that bounds the eastern side of Silicon Valley, acres of Salicornia pickleweed and Spartina cordgrass stretch out toward the shallow but choppy waters of San Francisco Bay. A boardwalk vaults over the marsh to overlook a section of muddy creek dubbed Rail Alley.

There, I sought something magical—a rail sighting. Just hearing the call wasn’t enough. In Burt’s words, spotting one by sight is elusive and inaccessible and fascinating for it.

So into the muck I would gaze. I felt that, with sufficient diligence, I could will a rail into walking across the creek. A form of magical thinking. Energy channeled toward the marsh that would return to me in the form of the bird I sought.

And one day in October 2005, that bird finally showed itself. Photos taken by my father show our family on the boardwalk. My five-year-old self scans the marsh, binoculars in hand, braced against the railing. Then, below us, a blurry rail makes its hasty strut through the creek.

One more species for my young but growing life list. Next to the rail’s entry in my copy of a Peterson field guide, a note in my mother’s handwriting lists the date and location of the sighting.

The records prove it really happened.

I’m asked when it happened—the breakup with E. I tell people that it was in “the end of August,” giving the impression that I do not recall the exact date. It suggests (intentionally) that I do not consider the date itself to be an important thing to remember. Compared to three and a half years spent together with her, I should really consider the exact day that it ended to be insignificant.

In reality I know the date by heart. I hold it in my thoughts often, especially as its anniversary approaches. I try to avoid telling anyone anything more specific than “the end of August,” because I do not want to give the impression that I remember the exact day, time, and place; I do not want to betray the truth that a part of me is still living in August 29, 2022.

For reasons I am still seeking to understand, I place an unusual emphasis on exact dates. August 29 was three days short of the start of the fall semester at New York University and ten days short of my birthday. By way of another example: December 7, 2016, the day I broke up with my first boyfriend, was the day of our wind ensemble’s winter concert; it was also precisely six and a half months after he and I started dating.

It’s a silly thing to remember. There’s no point to it. It was a fairly brief and somewhat unhealthy high school relationship; holding onto the date that it ended didn’t help me win any of the arguments with him that ensued in the following months. And when E. and I started seeing one another in early 2019, she was put off by the fact that I still remembered the date that my first relationship ended.

Of course she was right to find it strange. The thing I couldn’t explain to her at the time was that neither that old relationship nor the day it ended are nearly as important to me as the act of remembering for its own sake.

Memory is sacred; forgetting is anathema. I abhor uncertainty. I hate letting go. I am comfortable with the fixed, the discrete. I seek something to hold on to—a railing to grasp, a sturdy branch upon which to perch.

As such I end up affixing myself to precise-seeming things. Dates, times, locations—the boundaries between counties, the distinctions between species. These are precise, dependable—or at least they seem that way—and I fix myself to them because I find it difficult to accept that something that appears permanent may not remain so.

I keep boxes of old papers, sorted into polypropylene boxes and file folders organized by year and season. Sundry relics of the person I was at those particular dates and times: Polaroids, programs, receipts, tickets. I write on the back of wristbands from old concerts—when, where, who I was with—and file those away as well. And E.—oh, there is so much left of her. Sign-in stickers to her dorm building, receipts from a cross-country road trip, boarding passes from plane flights together.

Artifacts of my life accumulated in a private archive. Evidence that it all really happened.

These are the things that will not change, I tell myself. These are the breadcrumbs that will lead me back; if they cannot take me back, at least they will lead me somewhere familiar. Because God forbid I forget the way.

As my life list grew, its importance for me shrank. It was as if, in the course of seeking out new species, my attention snagged on the infinite sophistication of every bird I saw along the way. Building an impressive list can be accomplished in a few dedicated years; developing the true naturalist’s understanding is difficult to achieve in a lifetime.

I came to see listing as a juvenile tendency. Annual lumps and splits undermined the cosmic authority I had mistakenly ascribed to the list in the first place—it was, like the birds themselves, in a constant process of evolution.

The preoccupation with the numbers fell away from me like feathers in a molt. I sought a plumage of radiant subjectivity.

But even as my sensitivity to the subjective grew, I was still most comfortable approaching the world through the lens of the discrete. I was building a new understanding of the natural world, but I was building it on the same old, rigid scaffolding.

I moved to New York City in 2018; not until 2022 did I get around to going out in determined search of a Clapper Rail. An avid lister would have considered it a long-overdue tick on the list. I thought it overdue, too, but for different reasons: I had just moved out of Brooklyn to Manhattan without ever observing a Clapper Rail, despite the fact that it is one of Brooklyn’s birding specialties. The Brooklyn Bird Club’s newsletter is even named The Clapper Rail. (Also, I hadn’t seen or heard any on a couple previous trips to Clapper Rail habitat at Plumb Beach, and I wanted to make up for those misses.)

As in the case of Ridgway’s Rail, the Clapper Rail’s marsh habitat in New York City was once widespread but came to be widely eradicated. Brooklyn’s waterfronts became sites of industry and its offal. The site of Marine Park, where I decided to make my search, was previously occupied by a gristmill and a dump.

I visited the nature preserve at the Marine Park salt marsh for the first time on July 27 of last year (a month and two days before the breakup). I was awed first by the lush expanses of the grasses: their rustling on the dunes, their vibrant green glow in the shallow waters.

Two adult Osprey perched atop a wooden nesting platform, squabbling over a fish one of them had caught. Fledgling Willow Flycatchers zeeped, begging for food from their parents, from trailside trees fringing the marsh. Ahead of me on the trail, a rabbit paused on the gravel. Before I could finish lifting my camera, it had darted off into the grass.

On a distant nest platform, next to plastic trash woven into their nest, three juvenile Osprey sat bemusedly. Their peeps, chirps, and whistles intermingled with the distant squawking of the Forster’s Terns.

The trail bent toward some woods; the marsh became obscured behind a row of shrubs. The clouds, orange and purple vestments of the setting sun, spread themselves across the western sky. The bugs were biting and I was ready to turn back. I stopped on the trail and reached down within myself in an attempt to feel fully, the way I do when I find myself wishing that I could appreciate a place more fully than my brain is inclined to permit.

I made tentative contact with some feeling of relief. I sought to feel present there, on a trail between lush meadow and trees, low sandy dunes and tidal waters.

When I am feeling this way, I grasp again for the specific. I take photos; I denote times, places, taxa.

I attempt to construct a metadata of the self. If the self-cataloging is ruthless enough, I reassure myself, it will surely allow me to reconstruct the moment in some future time of need. Or perhaps I will find myself to be a jay that stores every acorn it finds against the coming winter only to starve before the snows come.

On this occasion, at least—July 27, 2022—the specifics I sought presented themselves to me. From beyond the layered curtains of the rushes, a harsh dry call rattled out of the marsh and into the summer evening’s heavy air: “chek-chek-chek-chek-chek-chek.”

A Clapper Rail, stalking somewhere in the reeds’ shaded dusk, issued its admonition. Elated, fervent, my mind scrambled to scoop up as much of it as I could carry, grains of moment between my fingers like fistfuls of sand.

Rallus crepitans, formerly Rallus longirostrus, the 465th species I had ever observed in the ABA Area, and the 173rd I had observed in Kings County, New York. The 211th species I recorded in 2022.

I did not know then that I was in the 38th month of what would end up being a 39-month relationship. I did not know that, some few weeks later, the structures of my life would unravel. I did not know what was slipping away as I trod the gravel paths and turned my ear toward the marshes.

What I do know and will always be able to know is that I observed a Clapper Rail, Rallus crepitans, the 465th species I had tallied in within the bounds of the ABA Area, the 173rd in that county, the 211th that year, vocalizing in Kings County, New York, on July 27, 2022.

Never mind that “species” is a shifting, arbitrary designation. Never mind that the ABA Area is a shifting, arbitrary region. Never mind the list. I don’t care about the list any more. It is not about the list and maybe it never was.

It is about how I did not know and could not have known the particular way in which things were about to change for me—and yet I was, and remain, perpetually alert to the prospect that any of it could fall away at any moment. And I am always desperate for some handhold to grasp when the floor drops out from beneath me.

I know it will happen again because it has happened before, so many times over. Sometimes it seems like it is all that happens. The clasp breaks and the necklace slips and I do not notice until I am home and the cherished thing is gone.

Rallus crepitans.

This is why I hold on so tightly: against the inevitability that what seems stable will shift, against the knowledge that what seems secure will slip.

465. 173. 211.

Maybe that is why it slips at all.

July 27, 2022.

It was a Wednesday evening during our last summer together.

I am not tracking all of these figures in real time as I walk around, if only for practical reasons. It’s the knowing that matters—the way that I can tell myself that these specifics exist, that somewhere they are being engraved in some distant ledger.

Fall migration unfolded in the weeks following August 29. I found myself wandering that season. I attended my classes irregularly. I spent days—sometimes days when I should have been focusing on schoolwork or cultivating new friendships—birding the green spaces of New York City. Four, five, six hours at a time in Green-Wood Cemetery or Prospect Park.

I took to writing by hand—with ink, more permanent than pencil—in postcard-sized pocket notebooks that I took with me wherever I went. I scratched down any thought that was clear enough to make out in the gloom. I recorded quotes overheard on the subway, sketched scenes that I thought might be worth looking back on at some future juncture—and, of course, which bird species I saw and how many of each. Every entry dated and timestamped.

I didn’t create anything coherent out of it. Whenever I tried, I seized up. More often, anticipating that paralysis, I avoided trying in the first place. What I did write was sparse, haphazard, but it kept me going. The knowledge that I would be able to refer back to something later, that these nodes could someday serve as anchors, was the comfort I needed.

That fall, I carried my camera, binoculars, and notebook through Brooklyn, gazing up at canopies and peering into foliage. Alone. Looking for things I could count on—or at least things that I could count. 🪶

bibliography

Chesser, R. Terry, et al. “Fifty-Fifth Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-list of North American Birds.” The Auk 131, no. 4 (2014): CSi–CSxv. https://doi.org/10.1642/AUK-14-124.1

De Groot, Dudley Sargent. “The California Clapper Rail, Its Nesting Habits, Enemies and Habitat.” The Condor 29, no. 6 (1927): 259–70.

Eddleman, W.R., and C.J. Conway. “Ridgway’s Rail (Rallus obsoletus), version 1.0.” Birds of the World (2020). https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.ridrai1.01

Finger, Corey. “Clap Louder! Clapper Rail at Plum Beach, Brooklyn.” 10,000 Birds (blog). October 10, 2010, https://www.10000birds.com/clap-louder-clapper-rail-at-plum-beach-brooklyn.htm

Nuttall, Thomas. A popular handbook of the birds of the United States and Canada. Boston: Little, Brown, 1905. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/38005872

Quady, Dave. “Farewell Clapper Rail, hello Ridgway’s Rail.” Golden Gate Bird Alliance (blog). August 11, 2014, https://goldengateaudubon.org/blog-posts/farewell-clapper-rail-hello-ridgways-rail

Ridgway, Robert, and Herbert Friedmann. “Family Rallidae: Rails, Gallinules, and Coots.” Bulletin of the United States National Museum no. 50, pt. 9 (1941): 39–41. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/7597880

U.S. Department of Commerce. Future Development of the San Francisco Bay Area, 1960–2020, report prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Washington, DC, 1959), 80–83. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b4030153&view=1up&seq=108